Jesmyn Ward

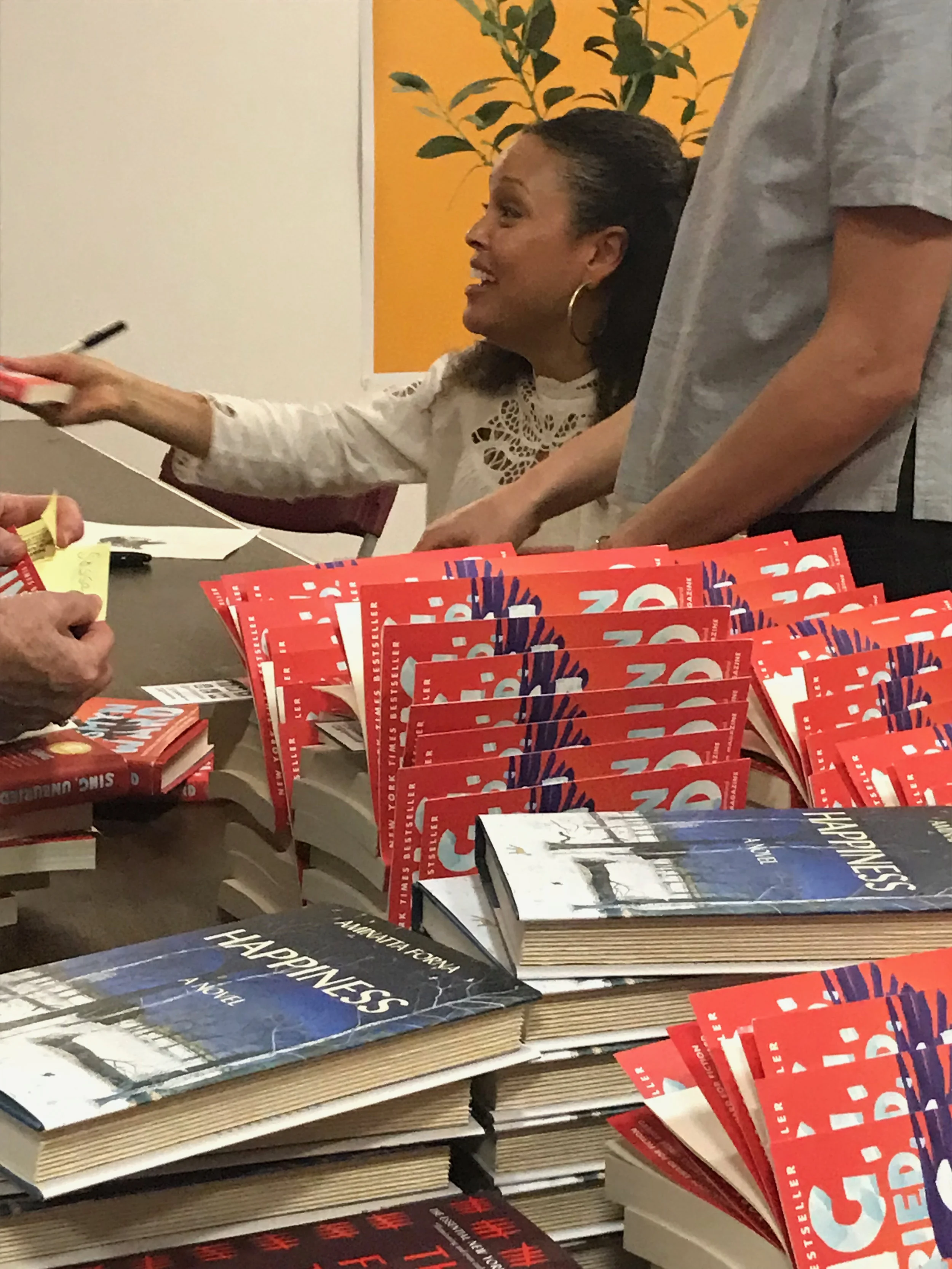

/Last night I had the profound fortune to meet Jesmyn Ward and to hear her discuss her most recent novel, Sing, Unburied, Sing, with Aminatta Forna. I have been an enormous fan of Ms. Ward's since reading Sing, Unburied, Sing early this year, after which I immediately read Salvage the Bones. She won the National Book Award for both books, the first woman ever to do so. I'm now reading her memoir, Men We Reaped, and have in my stack of to-reads the essay collection she edited, The Fire This Time.

If you're not familiar with Jesmyn Ward, please acquaint yourself for she is a stunningly gifted writer. Born in Oakland to Mississippi-bred parents, she was raised in DeLisle, Mississippi, as her parents moved back when Jesmyn was three. She was the first in her family to attend college, earning a BA and MA from Stanford. She also has an MFA from the University of Michigan and is now a professor at Tulane. Her family home flooded during Hurricane Katrina, and the storm, as well as south Mississippi, makes a regular appearance in her work.

A few months ago, when I heard she would be speaking here in DC, I bought a ticket as quickly as I could, and last night, no amount of fatigue or running around all afternoon with the kids could keep me from getting to the event 50 minutes early to obtain the best seat possible (thank you, dear T, for leaving work early to meet me in the parking lot and whisk the children away so I could scurry inside).

Like the lit nerd I most definitely am, I went armed with a tote bag full of Ms. Ward's books, sat in my seat like the eager student I also am, and felt positively star struck when she walked on stage. She is a luminous human with real humility and a quietly powerful presence. I could not help but beam at her throughout the evening and even mustered the courage to ask a question which, per my usual nerdiness (who remembers the three-part question I addressed to Gabrielle Hamilton?), turned into a two-part query that she was kind enough to answer in full.

She talked about how she writes, told us that beginnings are difficult for her but that she has to write linearly so soldiers on until the beginning is as it should be, that she is not the most confident writer, that her characters just come to her and then she follows them through their journeys. She doesn't like to write villians because “They’re flat and don’t engender empathy or interest. People are complicated. I don’t want my readers to feel easy emotions.”

She talked about why she writes, and why, despite her "love-hate" relationship with Mississippi, she moved back home after her brother's untimely death.

"I am trying to bring forgotten stories from the violent past back into the light and into the public memory and imagination." Stories before her time but also during, as the only black student at an all-white high school one of her mother's employers paid for her to attend. Stories about beloved men -brothers, friends, family- lost to poverty, drugs, racism, and happenstance.

Why?

"Because there is an effort to disavow and rewrite that history. That results in its continuation." Same root, same violence. We see it every day.

Regarding home. "I left as soon as I could. But I have a huge family, and they are all there. I was missing out, time I couldn't get back...Living at home keeps me honest and lends urgency to my work." For, as Ward softly averred, "The violence of America endures." When asked by Ms. Forna if she believed a truth and reconciliation effort a la Canada's might be needed here, Ms. Ward replied, "Yes." Firmly, resolutely, "yes. But is there the will? Not now."

Ms. Forna replied that indeed, "the absence of a will to reconcile with its past is shocking for visitors to America."

I hope desperately that in the immediate future we become willing, as a country, to own and atone for our past. I think efforts like the newly unveiled lynching memorial in Montgomery, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, are excellent starts but we need a national movement and a national reckoning. Ms. Ward suggested that we all read Edward Baptist's The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism post haste. I have ordered it already.

After reading several passages, shyly really, or perhaps just humbly, and answering all our questions, Ms. Ward received a standing ovation that brought me to tears. Then, in a largely polite fashion, people queued by number to have books signed and share a few words. Fortunately for the five books I had in my tote, the limit on signed copies was five. I had one inscribed for a dear friend and the others for starstruck me.

I was grateful to have the brief chance to be near Jesmyn Ward, to thank her for sharing her profound gifts, to wish her the best in her next endeavors. I was grateful to have a supportive spouse, to live in a city with such rich resources and opportunities, to bear witness to the strength and resilience and diverse beauty that really are what make America special.

I was pensive on my drive home, speechless really. Tom and the kids were playing Monopoly despite the late hour. I poured a bourbon and made some scrambled eggs and sat at our kitchen table considering that Ms. Ward might still be signing books and hoping that she felt full in good ways. That she could feel and ingest our gratitude and admiration and that perhaps those sensations might offer her some company when her confidence falters or the loneliness of a blank page is undesired.