Julie wrote this book after witnessing, during her professional tenure at Stanford, what can only be called a devolution: teenagers who arrived at college not as young adults but as kids; people more impressive on paper than in person; people who seemed less attuned to any budding sense of self than to their parents mapping their paths for them.

This was at Stanford, one of the most elite and competitive universities in the world. Arguably, these kids were those who’d most successfully navigated and completed the college admissions gauntlet our educational system presents: be the best at every turn, from the earliest age, and maybe you’ll be rewarded with a spot at a top-tier school.

And yet, what few until recently have stopped to ask is: At what cost?

In Julie's words, "when I spoke to the freshmen, they could tell me what they'd done but not why they'd done it...Chronologically, they were adults but they were largely incapable of fending for themselves...I began to wonder why childhoods were no longer preparing kids to be grown-ups. And what is getting in the way of people becoming who they really are?"

Let me be clear that Julie’s tone was not one of judgment but of concern. And, as a mother who’d found herself cutting her ten-year-old’s meat for him at dinner one night, also one of understanding. Too, as you probably suspect and as she stated, this is largely a middle- and upper-middle class phenomenon.

Julie noticed a dramatic increase over time of parents who brought their kids to college, helped them move in and settle, but then stayed -literally or virtually. And the kids were grateful. They didn’t want their parents to leave.

She recalled advising sessions during which students’ phones would ring multiple times, regularly they’d glance at the screen, say “Oh, it’s my Mom, do you mind if I take this?” and sometimes conference the parent in.

She described walking around campus and hearing students talking to their parents, often for the second or third or fourth time that day.

She started to see that helicopter parenting wasn’t just producing overly-scheduled, highly-accomplished people but also somewhat stunted kids who didn’t seem to know how to be their own selves, how to discover what made them tick, how to move through life independently.

Julie’s overarching concern is, as she said, “for humans:” for people who know who they are and can live authentically; who are tapped into their own minds and souls; who can embrace life as individuals rather than somewhat fearful automatons.

We have gotten to this “existentially impotent” state not out of neglect or lack of concern but because we parents are all trying so hard to do so right by our kids: “It’s part of the evolution of our love from umbilicus to our arms, from our breast to our early applause.”

But again, the questions: At what cost? To our kids? To ourselves?

*****

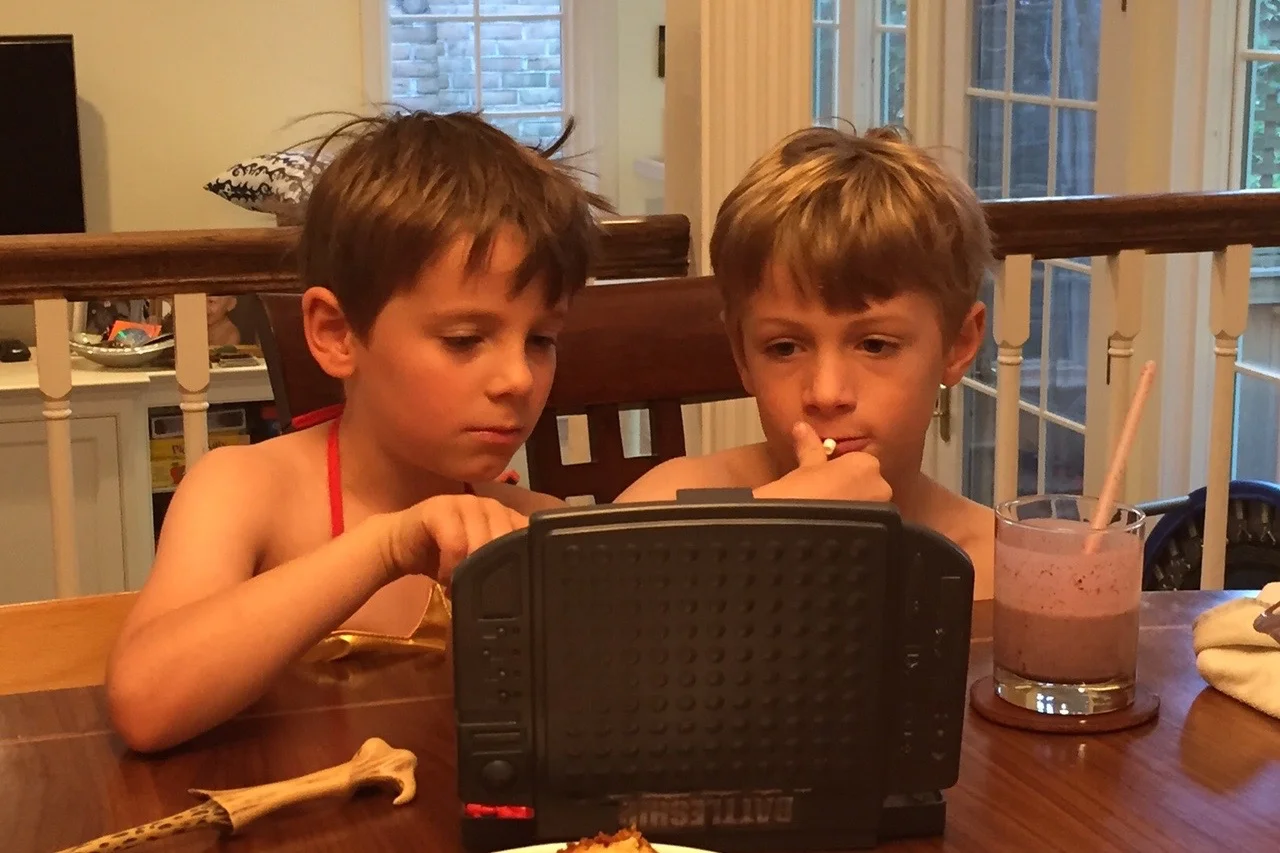

I still so clearly remember Jack’s first foray into team sports. He was almost three, and Oliver was a newborn. I signed Jack up for tot soccer, despite his protestations, because I thought it’d be nice for all of us to spend some time outdoors and for him to experience a group activity.

We gussied him in tiny shin guards and a cap (I did draw the line at cleats; no expensive cleats for two-year old soccer!) and bought a small, shiny ball pumped just so. Like Ferdinand under his cork tree, Jack proceeded to spend every practice in the backfield, picking flowers and identifying weeds instead of running laps and doing drills. I’m not sure he ever kicked his pretty ball.

I happened to find this all extremely dear and, never much of an athlete myself, didn’t care that he was not cottoning to soccer. He had tried to tell me that he wasn’t interested, yes?

When the “season” ended and the team leaders wanted to order trophies for the kids, I declined. The response, a subtle sucking-in of the breath, a vague grimace, surprised eyes, made me pause.

Jack had not played soccer, had not seemed to enjoy or even be interested in soccer, and so, in my opinion, did not deserve a soccer trophy. It made sense to me, but boy did I feel on the loser end of things. That sense of judgment -I was the only one to say no- was an interesting pill to swallow.

It also showed me that ignoring the Joneses can take a lot of determination, especially in certain environments.

*****

I’ve thought about that soccer trophy many times in the nearly six years since and about praise in general. “What’s the end goal?” I ask myself. "What character traits might I instill by bestowing undeserved finery and zealous acclaim? What message would I send my kids if I disregarded their innate interests in favor of my own? Don't I want them to feel the power of their own agency?"

When we do what others do, either out of a desire to keep up or to avoid disadvantaging our children in any way, without stopping to think about the long-term consequences, we might later rue them. Even if the ramifications come from nothing more than sincerely having loved our kids so very much. Which is certainly where the praise comes in.

Oliver has to work hard to read, and Jack struggles with the process of getting his many thoughts from brain to paper. Those are the efforts that truly deserve parental help and praise. Where many of us get tangled is in generously praising or overly assisting that which doesn’t warrant it; the things kids can do on their own and should. Or the things they don't do, a la tot soccer.

When I think about the times in my own life when I learned the most, when I really glimpsed a piece of my truest self, when I figured out how to access that and unearth more, I see that they were all times in which I was alone in the struggle but could call upon the support I’d always had: I’d been given a great foundation but was then left to forge my own path.

So why wouldn’t I want to do the same for my kids? What does it teach them if I willingly decide for them, clean up after them, take away their chances to fall and fail and pick themselves up?

I can do better in all these departments, and since hearing Julie speak, I've tried hard to backpedal the empty praise some, to remind the kids that doing things for their own pleasure is more important than mine (drawing a picture should make them happy; if I'm happy with it, that's great but shouldn't be the goal.), and to verbalize clearly that what I hope for them is that they find what makes them feel alive.

*****

One of the best gifts my parents gave me was saying, when I expressed my plan to change my major from environmental science to comparative religion, "That is SO cool." They didn't worry about how I'd support myself (or at least they didn't say that), they didn't say, "Hmm, that's odd. Are you sure?" They simply said, "That is SO cool." They said the same to my sister who majored in Acting and minored in Italian.

What that really acknowledged was a respect for the true passions we discovered and a belief in what we'd do by virtue of that.

I carry all these things with me as I raise my kids, and they have coalesced into:

- a total commitment to teaching the boys to listen to their own hearts;

- a total commitment to not judging them for who and what those hearts are;

- a strong belief that I can't ensure that they'll always be happy but I can help them discover the best ways to find that for themselves;

- a strong belief that if they are always valued for the individuals they are, happiness is more likely to follow;

- and a desire to have them emerge from my eighteen-year womb as whole people who do not want me to move to their college town with them.

Do I expect that they'll try hard and do their best? Yes. But their best isn't mine and ultimately, their lives aren't mine either. I hope this means I'm raising adults. I think Mrs. Lythcott-Haims might say I'm decently on my way.